Intro

this have been widely recognised by the scientific community for some thirty years. The necessary solution, which involves cutting and eventually eliminating net global emissions has been widely recognised for a long time. Despite this humanity as a whole has so far been unable to implement the needed reductions in net global emissions.

Solutions have been proposed. However, implementations have been very patchy and progress has been insufficient.

Climate change is a knotty problem. Solving it will involve changes in a number of areas including and especially economics, ethics, international agreements and constitutional changes. However, none of this will come about until and unless there is a wider understanding of the changes necessary and the ways they can and should be implemented.

With proper understanding, solving climate change will be doable.

Fundamentally climate change is one instance of the problems caused when technology advances faster than the necessary regulatory framework.

For all of human history the atmosphere has functioned as a free dumping ground for any and all emissions. The only cases where emissions of any sort were regulated was in those cases where localised negative effects were obvious.

Science is telling us now that the emissions of greenhouse gasses must now be regulated and brought under control.

Technology has advanced rapidly over the last two hundred years or so. Human nature is thankfully much more stable. Human societies have passed laws to regulate various aspects of society. Humanity has also developed government structures to enforce those laws. Hence as we come to the question as to how to regulate greenhouse gas emissions we are not starting from scratch. All that needs to be done is to adapt and update existing laws and methods of enforcement in order to deal effectively with greenhouse gasses.

In this paper we propose how to best adapt and change our legal structures and ways of thinking in order to achieve climatic stability.

We adopt a stepwise approach for the sake of clarity.

Balancing emissions in an island economy

For simplicity we will start with the relatively relatable case of an island economy without interactions with other countries. Let us call an example of a standalone economy “Stan”.

For Stan, in order to reach any desired level of emissions, we will first have to measure the sum total of emissions from Stan. Then we will have to measure and quantify the total negative emissions or sequestration of greenhouse gasses. The difference between the two will be the net emissions of Stan.

Any government wishing to reduce net emissions will have a number of options. These will include:

- Public Education.

- Passing Hard Laws to Prohibit emissions of certain kinds and or mandate actions to increase sequestration.

- Passing Soft Laws to discourage emissions and/or encourage sequestration.

Public Education is always going to be important. Indeed, a central reason for our writing this paper is as a means of educating both the public and policy makers as to the necessary or desirable changes required. Furthermore, any solution to climate change will involve costs of one sort or another. In order for the public to be willing to pay these costs , education of the public will be a necessity.

Hard Laws to prohibit certain emmissions or to enforce sequestration also can and should have a role. That being said certain types of emissions are deeply engrained in the fabric of society. Sudden change will likely be very difficult to enact and to gain public support . Hence the importance of soft or economic laws to discourage emissions and to encourage sequestration.

Balancing emissions is, in principal relatively easy in a closed system using an appropriate carbon tax. Emissions will be taxed at a rate sufficient to pay for equivalent sequestration and bureaucratic costs. Some emitters will cut down emissions or use alternative technologies. Those that do not will be taxed as above. The taxes will then be used for sequestration and thus we will achieve net zero emissions.

In its essence this is a simple mechanism which could lead to net zero emissions. Indeed, we are not aware of other mechanism, short of some cataclysmic event, which could lead to net zero emissions.

Of course, there will be some complications. We list some of them as follows:

- Assuming some sort of democratic society, the people would have to be persuaded that the costs involved are worth bearing.

- As the aim is to reduce emissions, we will need to maximize the ability of consumers to move consumption to non polluting alternatives. For if there are no alternatives, the carbon tax may reduce emissions slightly by raising prices, but, especially where demand is inelastic, emissions will not change much. An example may be useful here. In 2022 the total yearly electricity consumption in Israel was 77 terra watt hours. In order to produce that much electricity reliably, year-round using solar energy an area of approximately 300 square kilometers will be needed. Until and unless the Israeli government is prepared to allocate that much land or to pay the extra costs involved with dual use of land with solar, transferring to renewable energy will not be feasible regardless of the level of a carbon tax.

- Similarly to the above we will need reliable validated methods of measuring emissions and sequestration.

- The companies that will be taxed may reckon that it will be cheaper for them to influence the government or public opinion by whatever means they may find than paying the taxes. There is a history of companies with problematic products such as tobacco or oil using their economic resources to avoid or water down regulations.

- The costs of a carbon tax will be felt more by people of lower socioeconomic status. This may exacerbate resistance to a carbon tax.

These complications lead to the obvious conclusion that even such a simple and effective method as a carbon tax will have to be part a comprehensive plan to reduce emissions.

The cost of emissions

The benefits of a carbon tax primarily lie in the avoidance of much larger costs if emissions are not reined in.

The estimation of the economic costs of emissions is not easy and very few people understand much about it.

W find it useful to reference work published by the American environmental protection agency in 2016.

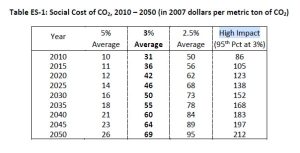

They published a table as follows:

It is necessary to explain the difference between the actual cost of the damages caused by climate change and the social cost.

The actual cost is simply the sum total of damages expected to be caused by emissions in the future. The social cost is based on the premise that people care less about future costs than current damages. Future damages are discounted by some discount rate for each year in the future. The effect of this is to create a massive discrepancy between actual damages and the social cost. The social cost is also completely arbitrary as the discount rate applied per year is a subjective value judgement.

The social costs specified for the year 2is can be seen in the following table published by the EPA summarising the social cost of emissions

| Discount Rate | 2.5% | 3.0% | 5.0% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Cost | $ 68 | $ 46 | $ 14 |